Opening hours:

Tuesday 10 am to 6 pm

Wednesday 10 am to 6 pm

Thursday 10 am to 6 pm

Friday 10 am to 6 pm

Saturday 10 am to 5 pm

Han Bing, Gao Brothers, Lu Fei Fei, Dai Guangyu, Zhang Huan, Qiu Jie, Wu Junyong, Chang Lei, Hung Tung Lu, Gu Wenda, Gao Xiang, Cang Xin, He Yunchang

“惊雷”布展现场

仓鑫作品

高翔和他的作品 |

Avec le lancement du nouveau livre de Ai Weiwei, intitulé Wei wei-isms, et de MAO, une iconographie complète. | With the launch of Ai Wei Wei’s new book Wei Wei-isms and MAO, the complete book of Mao iconography.

Vidéos | Videos:

Han Bing, Cao Fei, Zhao Liang, Hong Wai, Waza collective.

Exposition du | Exhibition from:

31 janvier au 27 juillet 2013 | January 31st to July 27th, 2013

Vernissage | Opening reception:

jeudi 31 janvier à 18h00 | Thursday, January 31st, 2013 at 6pm

Cet évènement inaugure le nouvel espace d’exposition permanent de l’Arsenal à Montréal. | This show inaugurates Arsenal Montreal’s new permanent exhibition hall.

Commissaire d’exposition | Curator Pia Camilla Copper

Commissaire associée | Co-curator Margot Ross

Media Coverage

The Gazette | John Pohl | February 22nd, 2013

Mao figures in contemporary Chinese art

Voir | Nicolas Mavrikakis | February 4th, 2013

La Presse | Nathalie Petrowski | February 4th, 2013

CBC news: Montreal at 6:00 | February 1st, 2013

Thunder out of China: Artists escape China’s censure and exhibit art in Canada

Radio-Canada | Radio | January 31st, 2013

Coup de foudre pour l’art contemporain chinois

Radio-Canada | Télévision | January 31st, 2013

La chronique culturelle du 31 janvier

Le Devoir | January 31st, 2013

Chinese Art Storms Arsenal Montreal

Arsenal Montreal January 31 to July 27, 2013

POSTED: FEBRUARY 12, 2013

“Like Thunder Out of China,” the first exhibition in Arsenal Montreal’s new permanent exhibition space, certainly wields a powerful force. Featuring 18 contemporary Chinese artists and artist collectives and 44 works in total—including paintings, drawings, photographs, videos and a sculpture—the show conveys political edge, as well as considerable technical skill and aesthetic pleasure.

According to co-curator Pia Copper—a Paris-based curator and publisher who has lived in China—the Chinese government can block art exports, so most artists get their work out of the country by either carrying it with them or by making digital art that can be printed elsewhere.

Not at all subtle is the one sculpture in the show, Miss Mao No. 3 (2006), a large stainless steel piece by the Gao Brothers. The government confiscated previous versions of Miss Mao (depicted as a young Manchu prince/princess with braids, huge breasts, a Pinocchio nose and the teeth of a vampire), says the show’s other co-curator Margot Ross, a Montreal art consultant who pitched this exhibition to the Arsenal.

Three artists who might be considered apolitical do have large paintings and drawings in the show.

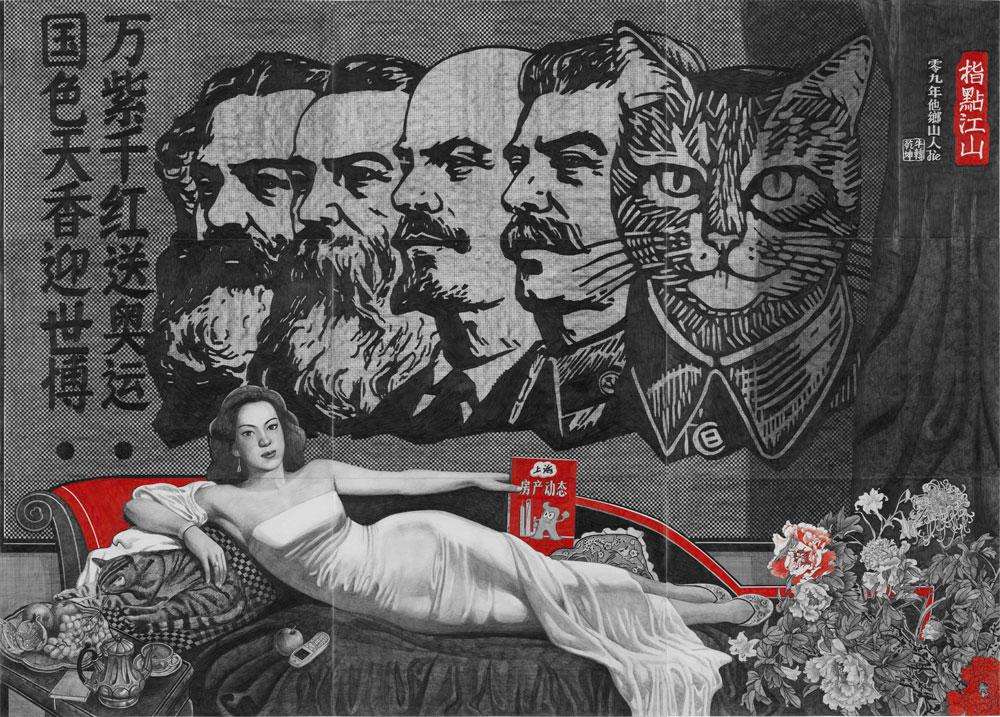

Qiu Jie crams figures and writing into what resemble overcrowded—but clean and readable—political posters in a Pop-art cartoon style, using only charcoal and a little gouache on paper. Mao—a variant of the name can be translated as “cat”—is portrayed in Woman and Leader (2008) as a feline in a lineup of serious male humans that includes Stalin.

Qiu Jie is more painterly in other charcoal drawings, but just as ambiguous. Mao in Winter (2011) shows the leader as a kind of a foppish post-hippie, again with a cat’s head.

Cang Xin makes charcoal self-portraits full of symbols of his spiritual quest on 650-centimetre-tall scrolls. He’s not overtly political, Copper says, but he believes that “if your being is in perfect order with the universe, the political order will also be in order.”

Gao Xiang paints beautiful-but-grim women and tiny men in Mao suits—a reference to officials—against a Chinese-red background. The artist, who came to Montreal for the opening, denied there is any political intent or symbolism in the work, calling himself a romantic. But he says he is disturbed by the imbalance in relations between men and women in Chinese society. He showed me a catalogue in which he juxtaposes his Who is the Doll? series of paintings, on view at the Arsenal, with photos of historic artworks in which men tower over their women. “Look,” Gao says, “the women are always smaller.”

The emasculated man reappears in Chang Lei’s Sanguinolency of Chinese Civilization No. 2 (2012), naked and sexless. Chang Lei, who was also present at the opening, says it is a self-portrait in which he represents the Chinese male as “without balls.” The elephant—he says that the term for this animal is pronounced in Chinese in a manner similar to the word for “reality”—dominates the background. It has a huge, vulvic mouth.

Again, the work doesn’t aim to promote misogyny. Rather, it is meant to refer to the lack of control that Chinese people have over their lives.

Chang says he is not afraid to criticize the government, but implied that it’s useless to do so. “The government has the control,” he says. “I’m not afraid to show my work in China, but the government can close an exhibition.”

Pornography is the excuse the government uses to censor the Internet, Copper says. He Yunchang’s photograph Ai Weiwei Swimsuit Print (2011) is a group portrait of men and women covered only by printed images of Ai Weiwei, the country’s best-known dissident artist, who has spent time in prison.

Zhang Huan writes his family out of history in a series of photographic self-portraits titled Shanghai Family Tree(2008). Zhang, whose family was blacklisted during the Cultural Revolution, had three calligraphers write texts about the “spirit of family” on his face, Copper says. As the faces turn black with calligraphic marks, apartment buildings appear in the background, marking the transition from village to city.

But there are stirrings of revolt. In Animal Farm (2009), a digital print, Chang Lei puts Communist leaders past and present on a reviewing stand. They preside over a parade ground crowded with animals—all of them in a state of alert.

“Animals sense an imminent change in the weather before humans do,” Copper says.

Located on a former shipyard and dry dock, the newly opened Arsenal Montreal seems an unlikely place for a major group exhibition of Chinese contemporary artists. Yet the setting, with its large industrial spaces and lack of pedestrians, is reminiscent of the experience in the once-peripheral Beijing art districts of Caochangdi and Dashanzi, where many of the eighteen artists in the show exhibit.1

Contemporary Chinese art in North America tends to attract viewers eager to sniff out subversion and suppression, seeking a clandestine peek into what they imagine is a repressive art world. Well, it isn’t, or not all the time, and simply repeating these clichés is problematic and facile, preventing a more nuanced understanding of how global and diverse the contemporary Chinese art world is.

The Gao Brothers confirm stereotypes of subversion in Miss Mao (2006), a grotesque, mercurial sculpture whose silvery surface is as alluring as her vampire teeth and swollen breasts are repellant. She does little to add nuance to our understanding of contemporary Chinese art. Yes, the sculpture is banned in China, but it is still seen in China. Mocking Mao by making him a woman is kitschy and short-circuits any opportunity to provoke insights into contemporary China. Miss Mao, like much of the Gao Brothers’ practice, is pure spectacle; the sculpture’s breasts are far less shocking than the thousands of dead pigs floating in Chinese rivers.

But something is stirring behind Miss Mao’s back. Han Bing’s series New Culture Movement (2006) is a set of six photographs of a man, woman, or child clutching a brick.

Han Bing. New Culture Movement, 2006; C-print; 28.5 x 18.5 in. Courtesy of Arsenal Montréal, Montréal.

Han a makes a clever satirical switch by replacing the expected prop, Mao’s little red book, with a big red brick. The central position of the figures, all in stoic poses with feet firmly planted, recall the oversized workers in Cultural Revolution–era (1966–76) propaganda posters. Now, though, the dream of socialism’s bright red future has been replaced by blaring market reforms made manifest across China with the breakneck pace of construction.

Han Bing visualizes the government’s notion of modest prosperity (xiaokang shehui) in the form of red bricks, symbolizing economic mobility even at the lowest social level. But bricks, as the film director Wang Xiaoshuai portrayed at the end of Beijing Bicycle (2001), are also useful weapons.2 In Han’s photographs the rough weight of bricks fills the people’s hands: might they realize the power they hold?

Comments

Comments