来源:燃点 文:Peng Zuqiang

Portikus, Frankfurt (Alte Brücke 2 / Maininsel, D – 60594 Frankfurt, Germany), Jul 12—Sep 7, 2014

In his most recent exhibition at Portikus Frankfurt, Simon Denny’s point of departure lies in a conference held by Samsung in Frankfurt in 1993, after which the company would go on to revolutionize its image and the state of the tech industry at large. Samsung’s then-chairman Lee Kun-hee gathered together the company’s top executives in Frankfurt—Germany’s financial capital and transportation hub—to hold a three-day meeting now known as the “Frankfurt Declaration” of 1993. The declaration announced the company’s shift to a “New Management” model: geared towards quality, development and internationalization. It was a catalytic moment for Samsung’s march towards international prominence.

A graduate of Frankfurt’s Städelschule (Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste), Simon Denny hails originally from New Zealand. His works and exhibitions often take the form of sculptures, archival works and installations, all exploring the history and development of enterprise, corporations and technological phenomena. Now, over twenty years after the “Frankfurt Declaration,” Denny’s work at Portikus researches Samsung in an attempt to explore the influence the conference continues to exert on the economy today.

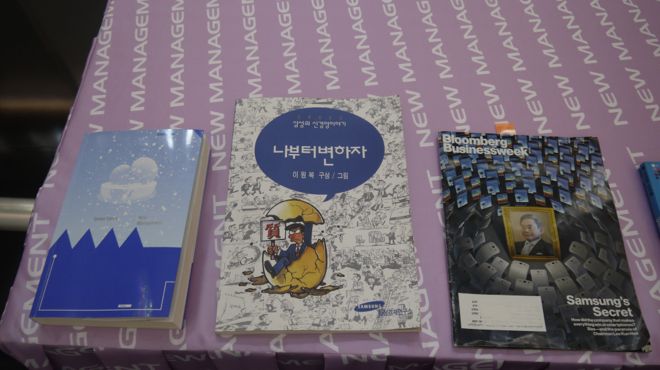

Placed in the center of the gallery is an executive office chair printed with a photograph of Lee Kun-hee speaking at the conference, along with a table, both similarly symbolic of a company conference space. In the process of research, the artist heard a rumor that Samsung had had a conference space somewhere in Korea, built specifically in memory of the “Frankfurt Declaration.” This exhibition, with its plexiglass and metal frameworks, is the artist’s re-imagining of that memorial meeting room. The farcical pairing of a forged Antonio Canaletto painting and a pink patterned tablecloth serve to undermine the importance the suspended space would otherwise assume, while each end of the structure is home to a pair of air conditioning units paradoxically connected to heaters: a futile circulation of air. What’s more, the air conditioners are branded with Samsung’s trademark slogans, which come across as absurd in this context—thinly veiling the artist’s true opinion of their bullishness. Phrases coined include “Change everything but your spouse and kids” and “Change begins with me”—representing a model of corporate propaganda that stresses the maximization of profit and efficiency, and implies the complex relationship between individual, family and career when it comes to the pursuit of success. Texts and photographs on the walls look back on the history of Samsung’s development, and readymade manga cartoons further illustrate the “New Management” philosophy. We find the Samsung of twenty years ago portrayed as a young wolf in the face of fierce lion and tiger competitors—companies like Sony, Panasonic and so on. The wolf says to himself, “One country alone isn’t enough. Only the strong survive. I must conquer an entire jungle of competition!”

The combination of objects and materials in this exhibition resonate with a strong sense of control. The black metal frame’s segmentation of the space conforms to the laws of symmetry. In Portikus’ exhibition space—once a church—this symmetry is especially noticeable. The texts and images hung on the wall parallel the rows of high church windows, and skyscraper models erected atop air conditioner packaging boxes look out from them at their life-size counterparts in the Frankfurt financial district. Perhaps it is only when we experience an association between the Samsung products on display and the Samsung products in our pockets that we can fully grasp what Denny is attempting to show us: the depth of an international corporation’s influence on the masses in an age of expanding global capital. And yet, with each new company-wide slogan, we note that the nature of this propaganda diverges completely from the advertising language we are accustomed to seeing in our everyday lives. The latter includes Samsung’s trademark slogans, which come across as absurd in this context—when we would otherwise think that the consumer and visual culture that advertising represents ought to be more closely linked to the corporate lexicon.

Samsung itself is frequently there within art exhibitions—usually via its flat-screen LCD monitors. The difference in this instance is that the company’s presence is not taken for granted. The exhibition includes textual records as well as objects symbolic of Lee’s famous speech, provoking a discussion of how products and other media can be harnessed to demonstrate Samsung’s management philosophy and ideas. Samsung products are displayed here to reflect the company’s guiding principles; the history of the physical evolution of Samsung cell phones is laid out on the wall to hit home the company’s hungry ambition for expansion: both are examples of objects demonstrating values. Conversely, in researching the management philosophy, one can indeed begin to see how these products physically embody the unceasing evolution of enterprise: i.e, values elucidating objects. In short, this is an exhibition concerned with the sequenced relationship between objects and the principles behind them, such that materials and materialism can shed light on one another simultaneously.

Denny has gradually built up his own language, consistently creating research exhibitions focused on commercial situations or events—a “management” model for artistic creation comprising of readymade objects, recycled material and fictional entities. As a series, Denny’s exhibitions all center on a unique commercial/technological/historical phenomenon, whether in his detached recording of events at Munich’s annual Digital Life Design (DLD) conference or his re-interpretation of the police raid on the home of Mega Upload founder Kim Dotcom. The artist’s exhibitions often include the reconstruction of an event or a space and a combination of readymades and texts to take the lead. These exhibitions represent one strain in the evolution of pop art’s reaction to the economic zeitgeist in the latter half of twentieth Century. This may be why Denny’s solo exhibitions tend to draw audiences in more than his appearances in group exhibitions or in the case of isolated displays of single works. However, though he lets us read an extensive account of Samsung’s family history, the artist only gives us limited freedom to sit back and consider it all. Our everyday cognitive indigestion in the face of excessive information is reflected in the exhibition’s heavy reading load, while oxymoronically, the very editing down of information is part of what the project preaches.